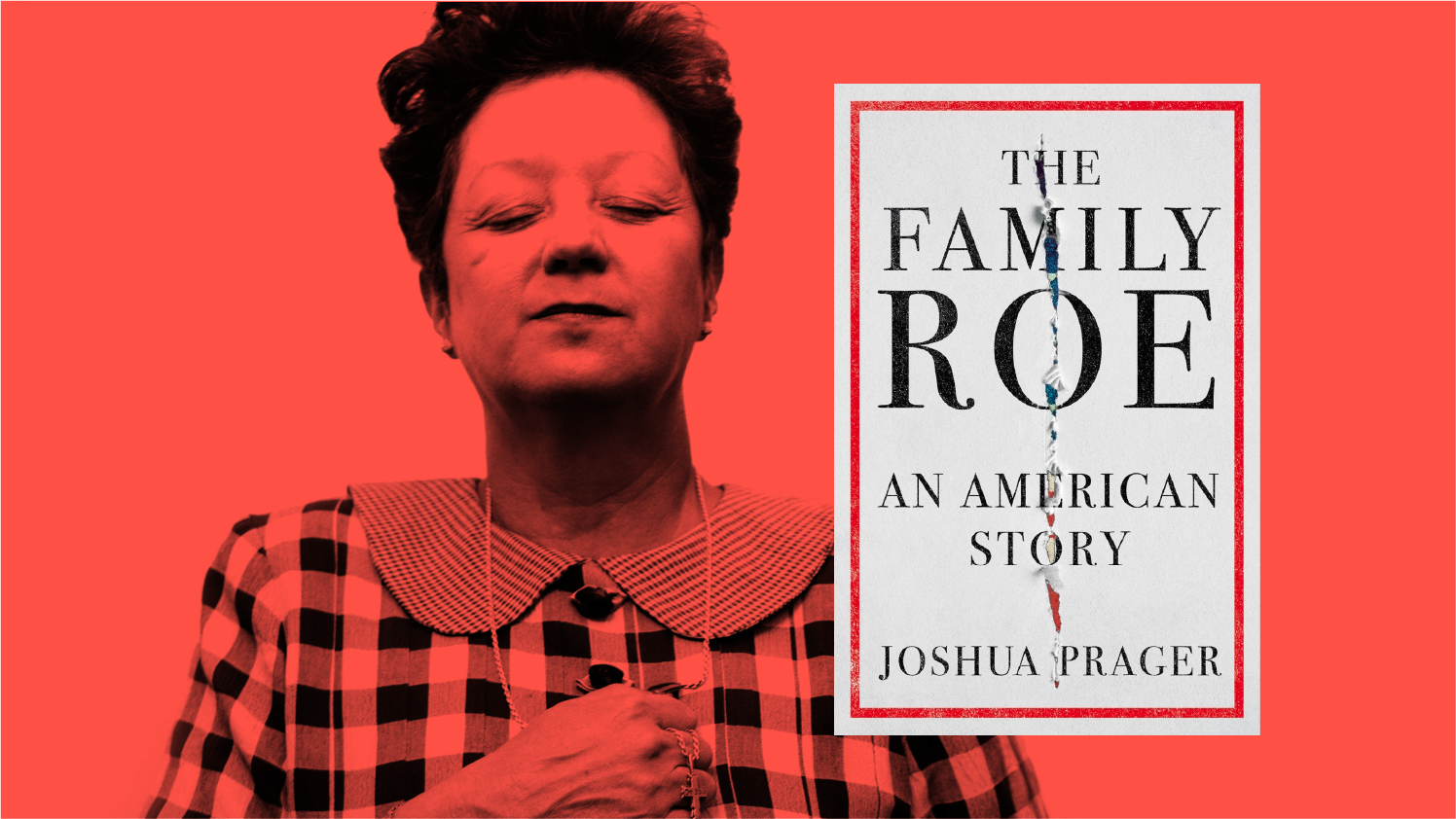

EXCERPT: 'The Family Roe' by Joshua Prager

The following is an excerpt from the prologue of Joshua Prager's book, "The Family Roe: An American Story." The book explores the Supreme Court’s most divisive case, Roe v. Wade, and the unknown lives at its heart.

On January 22, 1973, the Supreme Court decided Roe v. Wade, granting women the right to an abortion “free of interference by the State.”

The Court was undecided at first where in the Constitution to ground that right. It settled on the Fourteenth Amendment, ruling that it guaranteed Americans a right to privacy, and that a right to privacy secured a right to have an abortion.

There were some, even among the pro-choice, who assailed Roe’s reasoning. The feminist icon Ruth Bader Ginsburg would later argue, in an article she wrote while a member of the DC Circuit appeals court, that the right to abortion ought to be grounded in equality, not privacy. But others applauded Roe’s logic and its author, too, the Nixon appointee Harry Blackmun. Six of his eight fellow justices joined his opinion, and its longevity was assumed; when nearly three years later Gerald Ford nominated John Paul Stevens to the Supreme Court, the Senate did not even ask the judge his opinion of it.

But the fault line that is abortion in America began then to slip and heave, to produce tremors not only of politics and law but of religion and sex, the stuff that quakes the puritanical foundations of this country like little else. And today, to hear both pro-life and pro-choice tell it, the confirmation hearings of Supreme Court nominees are above all referenda on Roe.

Roe has come to dictate far more than judicial appointments. It is, as the legal philosopher Ronald Dworkin wrote, “undoubtedly the best-known case the United States Supreme Court has ever decided.” More, it is the most enduringly divisive. There is no surer indicator of political affiliation in America than Roe, the ruling a Rorschach test and a rallying cry, a means not only to party consensus but donor dollars—millions determined to uphold it, millions determined to overturn it.

Today, fifty years after the Court first heard arguments in Roe, the decision is hanging by a thread. Whether it falls or not, the American divide on abortion will remain. “Any victory, no matter how sweeping, will simply trigger a new round of fighting,” writes Mary Ziegler, a law professor expert on the American abortion debate. She adds: “the abortion conflict is a tale of hopeless polarization, personal hatreds and political dysfunction.”

Indeed, ours is a nation divisible by Roe. And as Blackmun noted in his preamble to the ruling, it is often personal experience—“exposure to the raw edges of human existence”—that determines which side of that divide one is on. The justice might have added that four years before he joined the Court, his daughter Sally had found herself unhappily pregnant in college.

Roe v. Wade was so named for its pseudonymous plaintiff, Jane Roe, and its defendant, Dallas district attorney Henry Wade. But at its heart, the case did not pit Roe against Wade; it pitted her against the fetus she was carrying. And the Court’s ruling alluded, if only obliquely, to the existence of the child that fetus became. Wrote Blackmun: “the normal 266-day human gestation period is so short that the pregnancy will come to term before the usual appellate process is complete.”

Blackmun was making a simple legal point: it did not matter that the gestation of a lawsuit is longer than the gestation of a baby. The case had not been rendered moot because its plaintiff was no longer pregnant. But Blackmun did not write that Jane Roe had given birth. And the public was left to assume that Jane Roe—whoever she was—had gotten the abortion made legally available to her.

Normally, a plaintiff is required to use her real name. The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure demand it. But, owing to the stigma of abortion, an exception was made in Roe, and Blackmun addressed it. “Despite the use of the pseudonym,” he wrote, “no suggestion is made that Roe is a fictitious person.”

Jane Roe was real. Her name was Norma McCorvey. And when, in 2010, I read an article that mentioned that Roe had been decided too late for Norma to have an abortion, I wondered about the baby she’d placed for adoption forty years before. I decided to look for her.

Months after Norma gave birth to that child in 1970, she met her lifelong partner, Connie Gonzales. Norma had just left Gonzales when, in June 2010, I visited Gonzales at her Dallas home. She told me that the stories Norma had told about herself were not true.

Gonzales’s home was due to be foreclosed on when I returned to see her the next year. She pointed me to a cache of papers that Norma had left behind in the garage and did not want. Looking through her speeches and letters, her holy cards and sheet music, I wondered not only about the Roe baby but about the other two daughters Norma had let go. I wondered also about Norma. Lifting a picture of Norma as a toddler atop a pony, I looked at the little house behind her up on piers and wondered, too, about her family rooted there on the banks of a Louisiana river.

Want to know more about who the "real" Jane Roe was? Hear Joshua Prager share more from his book on our podcast!

Plus, want to read more from "The Family Roe"? Find it at your local bookstore or on Amazon.

Posted by Joshua Prager